We all hear and talk about the effects of excess Regulation, a sometimes hostile political environment, and other external effects, affecting the costs of nuke plants, both the old ones and the new ones, and how that spills over into the ability of these plants to be profitable in today's weird energy market environment. But can you actually visualize it? It's true; sometimes a picture is worth a thousand words.

Background

We started digging the hole for Davis Besse in 1969, initial criticality was in July, 1977 and the plant was declared commercial in July, 1978. The collective memory opinion seems to remember we went commercial at a cost of about $400 million.

Back in those days Davis Besse was typical of "that kind" of nuke plant, where at the very top of the utility it was "just another power plant". And that's all the O&M budget we were going to get. In 1977 we were trying to run it with ~200 site staff, none of which were Engineering or even Licensing staff on site.

Needless to say, we had some growing pains. In fact when we finally did manage to burn up the first core and go into the first refueling outage, we had about 700 Design Change Requests, all stuffed into the first refueling outage. They ran the gauntlet of fixing typos on drawings to "Please finally fix the Aux Feed Pumps, when I need them they fail, and when I don't need them they start." (I think I wrote that one).

A word about the original Davis Besse site manning plan; we were not some extreme industry outlier. Much has been written and discussed in other places on this subject post TMI2 and in discussions about the founding of INPO. Basically for decades some electric utilities were known to be conservative and slow to adapt to change. With the rapid expansion of nukes into the utility fleet in the '60s and '70s some (stodgy is a word that has been used) utilities got into the nuke business that had a "run it until it breaks, fix the break, run it again" entrenched culture. And it was especially entrenched in the culture at the utility executive level, which directly controlled the plant budgets.

From their view, after watching extreme construction budget and schedule overruns, when the unit was declared commercial, it was time to "run the damn thing." They were not very open to hearing "we have some engineering design bugs to work out", their attitude was "if it runs, run it until it breaks." So we tried, but it never ran very long.

The other side of that coin was, by the time 60 or so plants were running pre-TMI2, there were a lot of ex-navy nukes working in these plants. At DBNPP half the original Operations staff was ex-navy nukes, along with several in Staff Management, more in trades like maintenance, C&HP, etc. We had grown up under the Rickover System. Do you really think we didn't understand what the nature of the problem was? Or what it would take to correct it?

Post TMI2

The largest single positive impact INPO had on nuke utilities after TMI2, was that the core of the INPO founders, both utility and navy, realized "we are all in this together; one more TMI and we are all done." They instituted the peer pressure philosophy at the CEO level with the message "If you think you are just running another power plant, and will continue to do it your way, we will get rid of you, so get on board or get out." Of course the other independent force in all this was the NRC.

The wheels of the required NRC post TMI2 changes moved faster than the wheels of the INPO changes, mainly because the NRC already had the infrastructure in place to mandate change, while INPO had to first create its structure and gain credibility with the utilities. Thus, inevitably, when Davis Besse got a serious wake-up call on June 9, 1985 with a Total Loss of All Feed Water event, it was still being run like "just another power plant." The NRC could mandate money being spent on the plant for post-TMI2 changes, but not for corporate attitude change. All that changed on June 9, 1985 in our case.

What I'm trying to figure out here is has the pendulum swung too far? And if so, why it happened? The money has already been spent and can't be recouped. But has it been spent on actual problems or perceived problems, and also has it been spent in proportion to the actual problem? I still can't figure out exactly why some of these plants say they are not making money and why it takes 700-800 employees to run one. What exactly are they all doing?

Anyway,

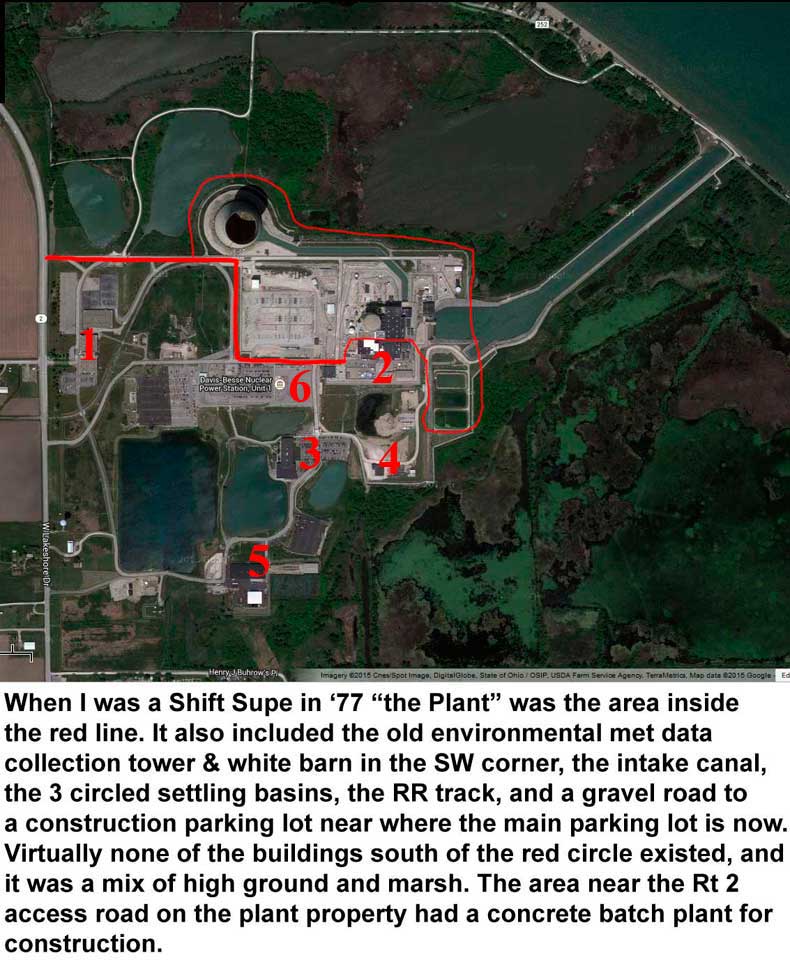

This is the plant in the 1978 time frame. Notice how full the employee parking lot is. The plant site access control point was a trailer just across from the Cooling Tower, and the actual plant access control point was the guard house adjacent to the employee parking lot. The left side of this picture is basically the end of the site boundary; there were no plant structures beyond that point.

The above is a recently current arial view of Davis Besse from Google maps, satellite view. Lets look at the numbered areas a bit closer.

Area 1

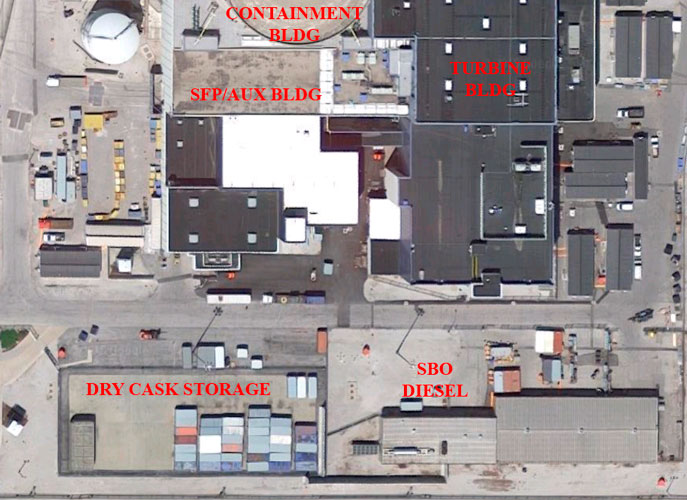

This view shows the Davis Besse Administrative Building (DBAB) built in the early '80s and driven by NRC post-TMI2 requirements, and also its annex at the top added later in the '80s. It also shows the DBAB emergency power block to the right side, basically a diesel generator. The DBAB actually met two functional requirements, providing the new space for some post-TMI2 NRC requirements and providing new office space for the crowded existing plant facilities. But the primary driver was the NRC post TMI2 requirement for a Technical Support Center (TSC) to integrate with new changes in the Emergency Planning (E-Plan) area and also provide space for new equipment to integrate with a new Emergency Operating Procedure philosophy for the plant Operators. Specifically that was computer equipment used to generate Safety Parameter Display Systems (SPDS) for the plant control room use. The facility also provided space for other areas that proved problematic during the TMI2 event, namely direct data links from the plant to NRC headquarters and a press briefing room, etc.

Much of this need has been well documented in thousands of pages of investigations and recommendations, and I don't want to repeat all that here. My purpose is "what was the problem, what was the solution, and was the cost of the solution justified by the problem." I'm not downplaying the seriousness of the actual technical problem. I'm not saying E-Plans were not in need of improvement; after all if your cultural basis is E-Plans will never be needed they are bound to need improvement. I'm not saying accurate technical information flow could not be improved, but to who and just why do they think they need it? What are they going to do with it? Take over operation when they are hardly qualified to operate the plant? Did the E-Plan itself actually fail at TMI2?

When a whole industry culture has been brought up to believe "It can't happen", and suddenly it is staring that whole industry right in the face that it has happened, rejection of that idea is more imbedded in the culture than reality. That happened at virtually every level and organization that touched this event. This imbedded denial was so strong that despite the fact that by about 3.5 hours after the event start, when the leak had been isolated, one third of of the top of all the fuel assemblies had melted into the bottom region of the core. And still it was denied by all involved until almost 5 years later when a camera was lowered into the core for an actual visual look.

So what actually drove the need for the Davis Besse Technical Support Facility? See the discussion for Area 1 from the left sidebar menu tab.

Area 2

(Area 2 working)

Area 3

(Area 3 working)

Area 4

(Area 4 working)

Area 5

(Area 5 working)

Area 6

(Area 6 working)